That’s good news. Odds are that some of those people will go back to closed media platforms after ~2 months; but the ones who stay help Mastodon and the Fediverse to grow.

The catarrhine who invented a perpetual motion machine, by dreaming at night and devouring its own dreams through the day.

That’s good news. Odds are that some of those people will go back to closed media platforms after ~2 months; but the ones who stay help Mastodon and the Fediverse to grow.

Thanks for sharing this data - it’s great.

It actually makes sense; if cat urine contained ammonia the smell would be gone once you washed your cat’s impromptu litterbox, since ammonia is both volatile and highly soluble. And yet it keeps stinking - this hints that there’s something else there producing that ammonia by decomposition. (Probably proteins. Cats eat a lot more protein than we do.)

Note: chlorine gas is the one that leaks from an open bleach bottle, and gives it a distinctive smell. The ones created by reacting bleach with ammonia are chloramines, considerably more poisonous.

I’m almost sure.

Your typical instance only defeds another as a last case scenario, due to deep divergences or because of blatantly shitty admin or user behaviour. But, past that, they’re still willing to let some shit to go through - because if you defederate too many other instances, with no good reason, you’re only hurting yourself.

That’s simply not enough to create those “corners”. Specially when all this “nerds vs. normies*” thing is all about depth - for example the normie wants some privacy, but the nerd goes all in, but they still care about the same resources.

*I hate this word but it’s convenient here.

Originally Anglish was a lot like Siegfridisch - a single guy (Paul Jennings), replacing borrowings with new expressions coined from native words, just for fun. Jennings framed this as how English would be if the Normans were defeated in 1066, and he published it in a satirical magazine (Punch).

It does look more serious nowadays, though. Anglish started out in 1966, and the people picking the idea up focused a lot on making it more consistent. (And also because Jennings wasn’t being as playful as Zé do Rock.)

Kind of off-topic, but can you believe that practically nobody knows Zé do Rock here in Brazil? Even if a chunk of his stuff is written also in Portuguese. (He also plays with the language, his “brazileis” is… weird, but in a good way, to say the least.)

I get what you say, and I agree; but when it comes to the average user I wonder if they’ll even get it. They don’t think on the grounds of a “protocol” or a “platform”, it used to be “site” and now “app”. They do it even with email, of all things, even if it’s one of the oldest cross-platform protocols out there!

They tolerate each other enough to get each into a corner and not interact much.

And yet that is not what we see in the Fediverse. Those “corners” don’t exist here.

That is correct but it does not contradict anything that I said.

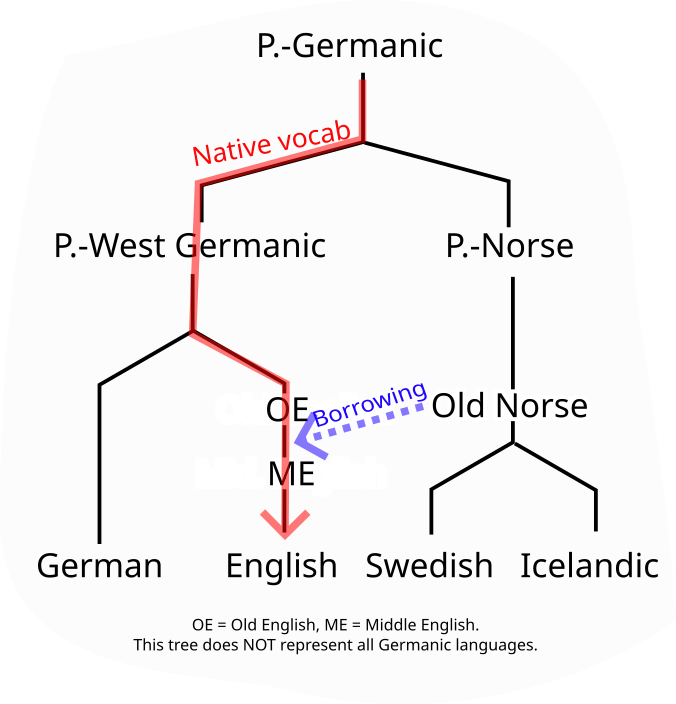

Even if Old Norse is Germanic, Old Norse words in English are still borrowings. “Borrowed” does not mean “not Germanic”, it means “not inherited”, both things don’t necessarily match.

This is easier to explain with a simple tree:

Only words going through that red line are “inherited”. The rest is all borrowing, the image shows it for Old Norse words but it also applies to French (even if French is related to English - both are Indo-European) or Japanese (unrelated) or Basque (also unrelated) etc. words.

But I digress. In Anglish borrowings from other Germanic languages should still get the chop, as seen here and here.

From a quick glance The Anglish Times does a good job not using those borrowings. The major exception would be “they”, but it’s rather complicated since the native “hīe” became obsolete, and if you follow the sound changes from Old English to modern English it would’ve become “she”, identical to the feminine singular. (Perhaps capitalise it German style? The conjugation would still be different.)

The people here and their attitude towards people who don’t agree with them are the problem.

And that’s a structural problem. The ActivityPub was supposed to allow both the “average person” and the “nerd” to coexist in the same platform, without one getting too much in the way of the other; it doesn’t.

I’m not sure on a good solution for that.

It’s all fun and games until venture capital kicks in, and exploits that central user data store to further centralise the rest of the network. Even then yes, I think that Mastodon has a lot to learn with Bluesky, on how to make user experience smoother.

so Germanic words are fine

Not all Germanic words; it depends on how they found their way into the vocabulary. For example something like “sky” should be still removed, even if Germanic - because it’s an Old Norse borrowing.

That’s an interesting experiment. I like how it “vibes” from informal to ancient.

“Friendly” and “land” are inherited, not borrowed. Those are two different processes and Anglish only gets rid of the words from one, not from the other.

“English” is not a mix; “English vocabulary” is. (Just like the vocab of most other languages.) A language is not just its vocab just like a mammal is not just its fur. The core of the language (its grammar) is pretty much what you expect from a Germanic language after some aggressive erosion of the case system.

English didn’t get many words from “German”; the inherited vocab is from “Proto-Germanic”. The name might be similar but they’re different languages, Proto-Germanic is the parent of English, German, Swedish, Icelandic, Gothic, etc.

People often point out the “French” (actually a mix of French and Norman) loanwords in English. Sure, there’s a lot of them, but as Anglish shows they aren’t structurally that important. On the other hand, the text couldn’t get rid of “they”, even if it’s a borrowing from Old Norse - the old third person plural “hīe” would probably have ended as “she”, just like the feminine singular.

EDIT: if the downvotes are due to some incorrect piece of info, please, say it. I tried to make the comment as accurate as possible, but something might’ve slipped, dunno.

Alternatively, if something that I said is unclear, please also say it and I’ll do my best to clarify it.

Federation woes?

Your comment has a different take though, and adding value to the discussion, it isn’t just the same as I said. Both are complementary.

Even more accurately: it’s bullshit.

“Lie” implies that the person knows the truth and is deliberately saying something that conflicts with it. However the sort of people who spread misinfo doesn’t really care about what’s true or false, they only care about what further reinforces their claims or not.

Predictable outcome for anyone not wallowing in wishful belief.

The image is simplifying it, but Italian borrowed the word from another Romance language, called Venetian. Latin sclauus /'skla.wus/ “slave, serf, servant” → Venetian scia(v)o /'stʃa(v)o/ “slave”→“bye”. Then Italian borrowed it from Venetian, and it ended as ciao /tʃao/ because Italian hates that /stʃ/ cluster.

The meaning evolved this way because of mediaeval humility expressions, like “mi so’ sciavo vostro”. It means literally “I’m your servant”, and it implies that I’m eager to fulfil some request that you might have.

A similar expression pops up in Southern German; see servus.

Sorry! I have a tendency to shift to technical vocab midtext, so it’s likely my fault.

I’ll use the comment to clarify some terms:

If anything else is unclear feel free to ask away!

I also wonder if some of these are actually false cognates, or if there is a much earlier common origin with false associations that came afterwards

Common but old origin tends to make words diverge over time. Compare for example:

| Old languages | Modern languages |

|---|---|

| Proto-Germanic */fimf/ | English ⟨five⟩ /'fa͡ɪv/ |

| Latin ⟨quinque⟩ /'kʷin.kʷe/ | Italian ⟨cinque⟩ /'t͡ʃin.kʷe/ |

| Proto-Celtic */'kʷen.kʷe/ | Irish ⟨cúig⟩ /'ku:ɟ/ |

| Sanskrit ⟨पञ्चन्⟩ /'pɐɲ.t͡ɕɐn/ | Hindi ⟨पाँच⟩ /'pɑ̃:t͡ʃ/ |

All those eight are true cognates, they’re all from Proto-Indo-European *pénkʷe. But if you look only at the modern stuff, those four look nothing like each other - and yet their [near-]ancestors (the other four) resemble each other a bit better, Latin and Proto-Celtic for example used almost the same word.

They also get even more similar if you know a few common sound changes, like:

In the meantime, false cognates - like the ones mentioned by the OP - are often similar now, but once you dig into their past they look less and less like each other, the opposite of the above.

They also often rely on affixes that we know to be unrelated. For example, let’s dig a bit into the first pair, desert/deshret:

Suddenly our comparison isn’t even between ⟨desert⟩ and ⟨deshret⟩, but rather between /seɾo:/ and /ˈtʼaʃɾa/. They… don’t look similar at all.

* see here for the word in hieroglyphs.

Other bits of info:

At least for my ex-fiancée it was about the link between husband and wife, plus tradition. It was basically “I’m married, you see?”. Just like a ring.

(We talked a fair bit about this stuff, as back then I was planning to add my maternal surname to my legal name. She was OK taking either surname.)